Typhoid Mary, North Brother Island’s Most Infamous Resident

As the site of a quarantine hospital, North Brother Island was naturally the site of many small, personal tragedies. But two of its most infamous tragedies were of historic proportion.

The first had to do with a woman named Mary Mallon, better known as Typhoid Mary. An Irish immigrant, Mallon worked as a cook in various households across New York City and Long Island. And everywhere she went from 1900 to 1907, people got sick with typhoid fever — and many died.

Mallon didn’t know it, but she was an asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever. One of the families that Mary had worked for hired New York City Department of Health sanitary engineer George Soper to investigate, and Soper tracked the typhoid trail to Mallon.

Soper established that all 22 cases of typhoid fever in the New York City area could be traced to Mary Mallon, which is where she got her nickname. She was promptly exiled to North Brother Island, but Mallon fought back — she couldn’t believe that she was spreading a disease which she had never had.

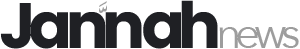

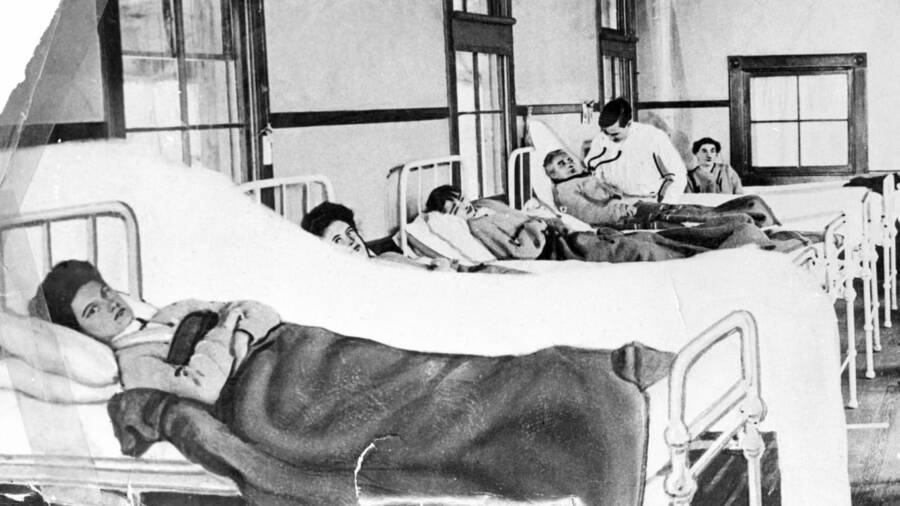

Public DomainMary Mallon in quarantine on North Brother Island, after she’d been dubbed the “most dangerous” woman in America.

Indeed, Mallon was able to secure her release in 1910 by promising that she’d never serve food again. But when an outbreak of typhoid fever reoccurred in 1914, Soper was able to trace it to places where Mallon had worked. She was sent back to North Brother Island, where she lived until her death in 1938.

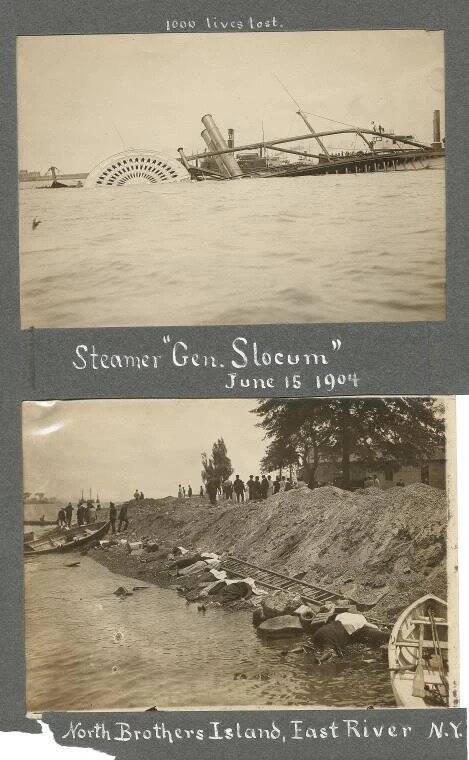

As Mallon was sickening her clients the early 1900s, North Brother Island bore witness to another tragedy: the 1904 sinking of the PS General Slocum.

The Wreck Of The PS General Slocum

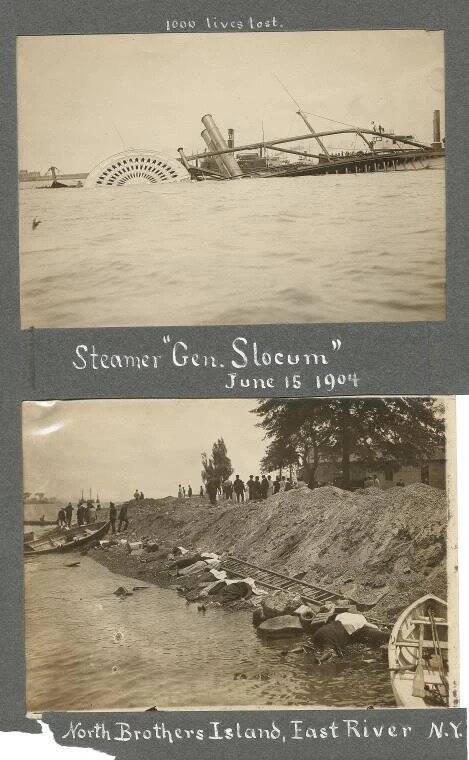

On June 15, 1904, some 1,358 passengers and 30 crew members set sail up the East River, en route toward a picnic site on Long Island. The boat was packed with jubilant men, women, and hundreds of children, mostly German-Americans on their annual outing to celebrate the end of the school year.

But the mood turned tragic when the boat suddenly and inexplicably caught on fire as it passed 97th street. Smithsonian Magazine reports that the boat’s fire hoses were rotten and quickly burst, rendering them useless. The crew rushed to tell the captain that there was a “blaze that could not be conquered,” a fire so bad that it was “like trying to put out hell itself.”

The captain tried to steer the ship toward North Brother Island in hopes that it could safely beach sideways so that the passengers could scramble off. But the fire grew larger and larger. Passengers threw themselves into the water, but most could not swim and were further hindered by their heavy clothing. Even passengers who managed to get their hands on life vests were largely doomed, as the vests — like the fire hoses — were rotten.

From the shores of North Brother Island, hospital staff watched in horror. Many of the hospital staff were able to assist the survivors. But not much could be done. Just 321 passengers survived, and the bodies of the dead washed up on the island’s beaches.

Until the 9/11 attacks, the sinking of the PS General Slocum in June 1904 was the worst loss of life in New York City history.

New York Public LibraryBodies on North Brother Island after the sinking of the PS General Slocum on June 15, 1904.

Despite these shadows of tragedy, North Brother Island remained a working hospital, in one way or another, until the 1960s. After World War II, it supported veterans and subsequently served as a treatment center for people with heroin addictions. But in the 1960s, North Brother Island was seen as too cumbersome and expensive to continue operating.

It closed in 1963. Then, a surprising new chapter for the island began.

North Brother Island Today

Today, North Brother Island is a strange oasis situated on the East River. The 25 buildings spread out across the island are decaying, making the island dangerous for humans — and perfect for birds.

As the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation explains, birds like gulls, herons, cormorants, and egrets have thrived on the abandoned island. (As well as on nearby South Brother Island.)

Indeed, it’s complicated for humans to visit North Brother Island today. First of all, there’s only a small visitation window in the autumn (which falls between shorebird breeding season and winter). Second of all, all visitors must have a “compelling academic and scientific” reason for visiting.

For that reason, very few people have stepped foot on North Brother Island in the past 60 years. But you can get a rare glimpse of the island in the gallery above.

There, you can see echoes of the island’s former life in photos of abandoned buildings, rusty spiral staircases, crumbling pilings, and more.