Inside The Dancing Plague Of 1518, History’s Strangest Epidemic

In the summer of 1518, the dancing plague in the Holy Roman city of Strasbourg saw some 400 people dance uncontrollably for weeks on end — leaving as many as 100 of them dead.

On July 14, 1518, a woman named Frau Troffea from the city of Strasbourg in modern-day France left her house and began to dance. She kept going and going for hours until she finally collapsed, sweating and twitching on the ground.

As if in a trance, she started dancing again the following day and the next day after that, seemingly unable to stop. Others soon started following suit and she was eventually joined by some 400 other locals who danced uncontrollably alongside her for about two full months.

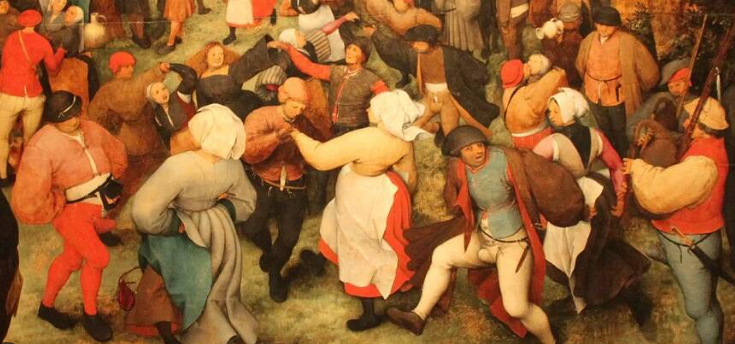

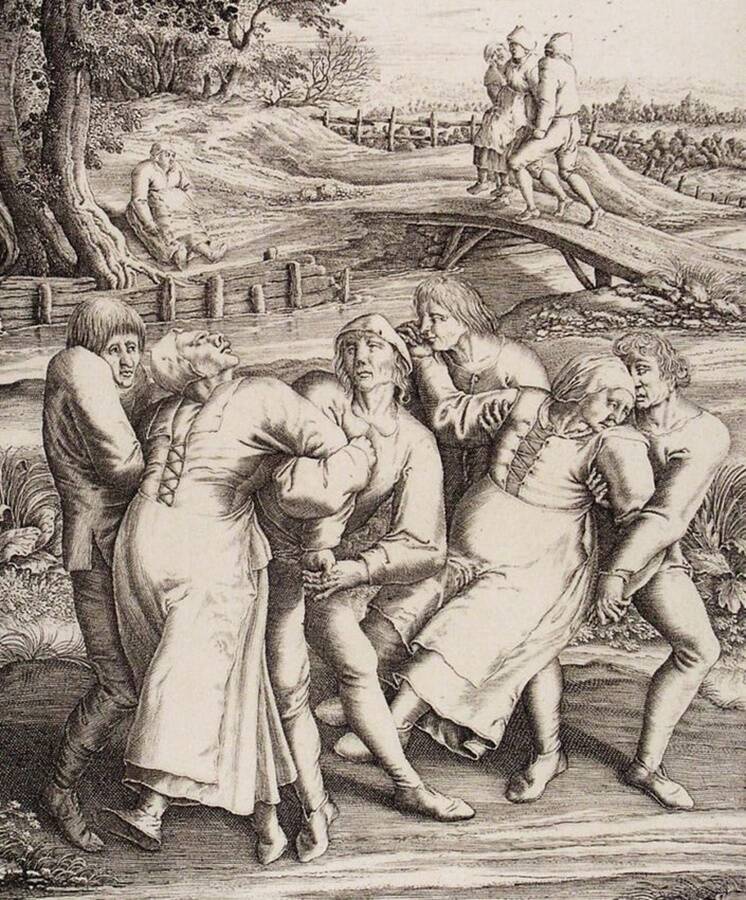

Wikimedia CommonsThe dancing plague of 1518 may have caused the deaths of more than 100 people in modern-day France who simply could not stop moving for days or even weeks on end.

No one knows what caused the townspeople to dance against their will — or why the dancing persisted for so long — but in the end, as many as 100 people died. Historians dubbed this bizarre and deadly event the dancing plague of 1518 and we’re still sorting through its mysteries 500 years later.

What Happened During The Dancing Plague Of 1518

Though the historical record of the dancing plague (also known as “dancing mania”) is often spotty, surviving reports give us a window into this unusual epidemic.

After the dancing plague commenced with Frau Troffea’s fervent-yet-joyless marathon of movement, her body eventually succumbed to severe exhaustion that left her in a deep sleep. But this cycle, much to the bewilderment of her husband and onlookers, repeated every day no matter how bloody and bruised her feet became.

Unable to summon any rational explanation, the crowds of people who witnessed Troffea’s dancing suspected it was the handiwork of the devil. She had sinned, they said, and was therefore unable to resist the powers of the devil who had gained control over her body.

But as quickly as some had condemned her, many townspeople began to believe that Troffea’s uncontrollable movements were divine intervention. Locals in the area believed in the lore of St. Vitus, a Sicilian saint martyred in 303 A.D. who was said to curse sinners with uncontrollable dancing mania if angered.

Wikimedia CommonsDetails of a 1642 engraving by Hendrik Hondius, based on Peter Breughel’s 1564 drawing depicting sufferers of a dancing plague in Molenbeek.

After suffering several days of non-stop dancing and with no explanation for her uncontrollable urge, Troffea was brought to a shrine high up in the Vosges Mountains, possibly as an act of atonement for her purported sins.

But it didn’t put a stop to the mania. The dancing plague swiftly took over the city. It was said that about 30 people quickly took her place and began dancing with “mindless intensity” in both public halls and private homes, unable to stop themselves just like Troffea.

Eventually, reports say that as many as 400 people began dancing in the streets at the dancing plague’s peak. The chaos continued for some two months, causing people to keel over and sometimes even perish from heart attacks, strokes, and exhaustion.

One account claims that there were upwards of 15 deaths every day when the dancing plague reached its height. In the end, about 100 people may have died thanks to this bizarre epidemic.

However, skeptics of this outrageous tale have understandably questioned how exactly people could dance almost continuously for weeks on end.

Myth Versus Fact

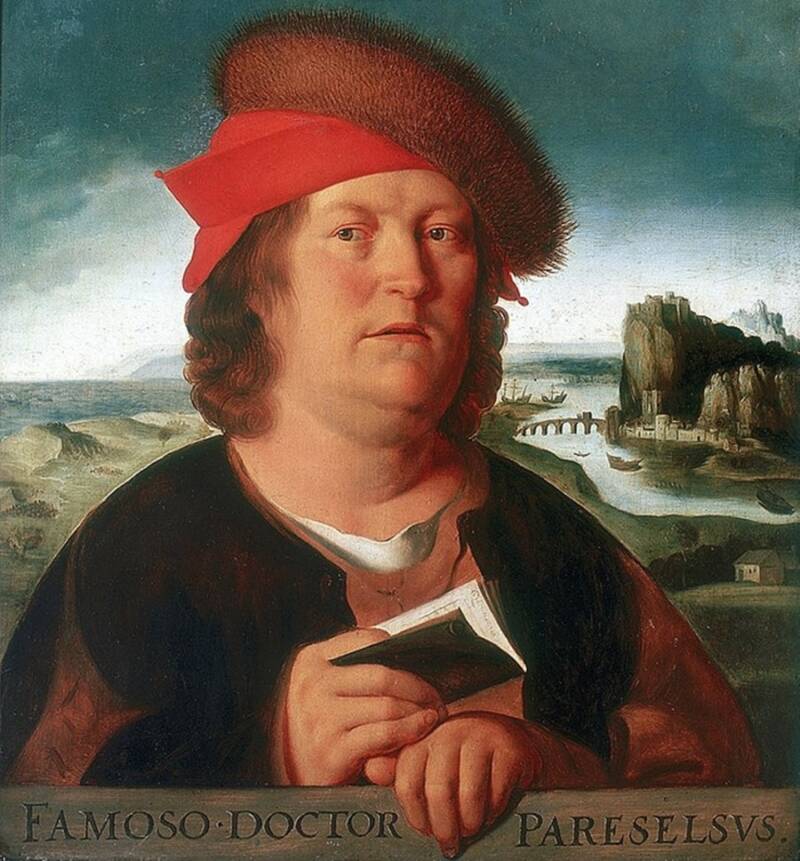

Wikimedia CommonsMedieval physician Paracelsus was among those who chronicled the dancing plague of 1518.

In order to investigate the plausibility of the dancing plague of 1518, it’s important to start by sorting through what we know to be historical fact and what we know to be hearsay.

Modern historians say there is enough literature surrounding the phenomenon to corroborate that it did actually happen. Experts first uncovered the dancing plague thanks to contemporaneous local records. Among them is an account written by the medieval physician Paracelsus, who visited Strasbourg eight years after the plague struck and chronicled it in his Opus Paramirum.

What’s more, copious records of the plague appear in the city’s archives. One section of these records describes the scene:

“There’s been a strange epidemic lately

Going amongst the folk,

So that many in their madness

Began dancing.

Which they kept up day and night,

Without interruption,

Until they fell unconscious.

Many have died of it.”

A chronicle composed by the architect Daniel Specklin that’s still kept in the city archives described the course of events, noting that the city council came to the conclusion that the bizarre urge to dance was the result of “overheated blood” in the brain.

“In their madness people kept up their dancing until they fell unconscious and many died.”